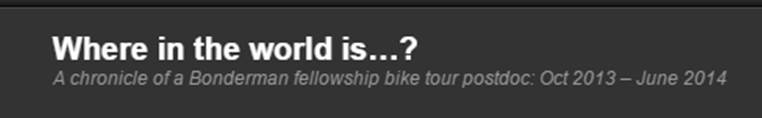

One dark and rainy night during my commute home from work, I was scrolling through the endless feed of images on Instagram-as one does- when I discovered a young biologist with a bright sunny face and captivating feed:

@biologistimogene – Imogene Cancellare – Wildlife biologist, conservationist, starving artist, optimist. Adventures welcome. Photos my own.

With 5,184 followers, I quickly joined the ranks of admirers. I gobbled up Imogene’s video shorts and inspiring selfies in the field. I felt transported into the world of a Wildlife Biologist.

With so many awesome posts of her nonchalantly holding lizards, snakes, and large mammals it is no wonder Instagram featured her in their “Scientists in the Field”

Before I knew it, 30 minutes had passed and it was time to get off the bus.

I walked home in the rain, head buried in the phone. I couldn’t stop scrolling. What I really appreciated about her feed were not just images and videos, but the amount of information and detail she shared with her followers which gave educational context to everything she posted.

A true educator’s spirit.

I stayed up through the night reading everything I could find about her career in Wildlife Biology.

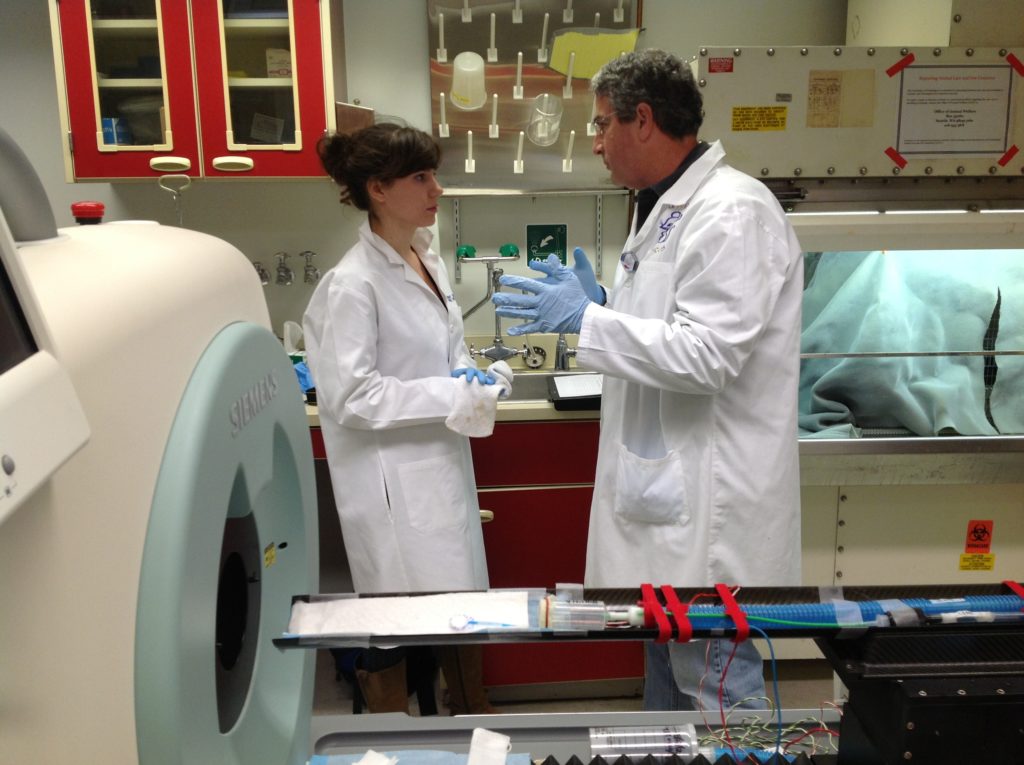

Imogene is currently a Research Technician working in the Lance Lab within the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory at the University of Georgia and has a B.S. in Animal Science from North Caroline State University (2010) and an M.S. in Biology from West Texas A&M University (2015).

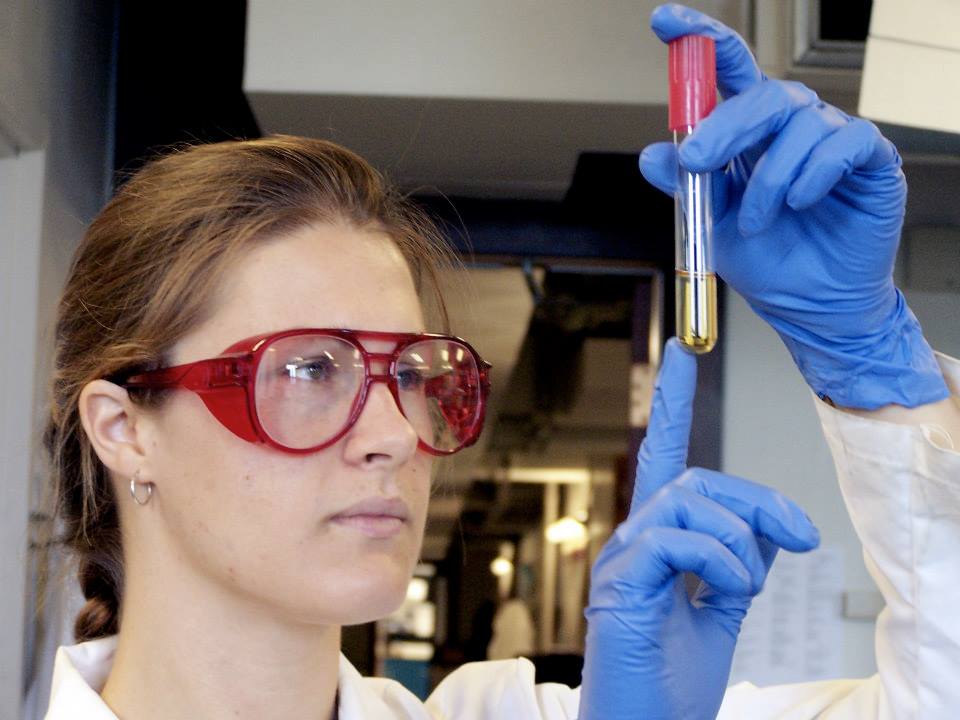

As a research technician, she assist with a variety of molecular and ecotoxicology projects across an array of taxa with a particular focus on salamanders and newts. Her work doesn’t stop there!

Bill, from Southwest Jaguars, did an excellent Q&A with Imogene in which, through a series of 12 questions, she generously shared about her research with meso-carnivores and other charismatic mega-fauna. As the Q&A came to an end, I grew sad that it was over. Naturally, I had more questions of my own. By the powers of Social Media, I reached out and asked Imogene my questions!

It is without further ado that I present to you:

Woman Scientist Interview with Imogene Cancellare – Wildlife Biologist

What type of scientist do you consider yourself?

My education falls in the areas of ecology, conservation, wildlife management, and genetics. I’m a wildlife biologist, but I also consider myself a conservation biologist and a landscape geneticist. I’ve been called worse.

What is your earliest memory of being hooked by science?

I remember being fascinated with amphibian metamorphosis as a child. Every summer I would watch frog and toad eggs hatch and watch daily as the tadpoles slowly changed into froglets, then into terrestrial adults. I didn’t realize at the time that this could be anything other than curiosity- I just assumed that people who liked animals were veterinarians. However, when I was in fifth grade my elementary school hosted a science fair, and I was excited to find that people actually tested and/or manipulated the things they found in nature. I created a project to evaluate the causes of fighting in roosters during certain seasons. While I didn’t place in the competition, and the experimental design was terrible, I had so much fun performing observations and testing interactions, logging my findings, and talking to adults about testosterone surges.

#tbt to the time I determined I probably wouldn’t be a fisheries biologist

Was there any one person that inspired you?

My grandfather was a medical doctor and radiologist, and one of the most intelligent people I have ever met. I dedicated my thesis to him because of his love for science. He taught me that higher education is the most important thing you can do and that biology is endlessly spellbinding. His respect for the scientific process and desire to never stop learning heavily impact my goals as a scientist.

When I was in college and trying to decide what field best suited my interests as well as addressed the needs of wildlife conservation, I decided to take a trip by myself to Washington, DC for an annual fundraiser for the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF). CCF is an amazing conservation organization focused on cheetah conservation in the wild as well as addressing the needs of human communities so human and wildlife can coexist. It’s a really active way to address conservation needs, and the founder and CEO, Dr. Laurie Marker, has an unmatched focus towards this effort. I have a lot of respect for her, as she is a self-made career woman, scientist, and top-notch conservationist. I got the chance to privately sit down with her in DC (and Dr. Stephen J. O’Brien, a world-class geneticist who at the time I didn’t realize is basically famous) and speak with both of them about my career goals. At that time I was divided on my interests in veterinary medicine and wildlife biology, and I asked her what avenue most strongly matched the needs in conservation. She smiled at me and said that if my goals were to, for example, save a species, that I could always collaborate with a really good veterinarian and be free to simultaneously work in other areas. It was a subtle suggestion, but it spoke volumes. I’m so thankful for that private meeting because I got to sit down with two renowned scientists and receive advice that has really spearheaded my career focus.

Dr. Laurie Marker with cheetah “Chewbacca” (CCF’s ambassador cheetah that was rescued from a trap on a livestock farm and raised by Dr. Marker)

Cheetah Conservation Fund, Namibia

What did you study during undergrad? Did you know what you wanted to study before beginning?

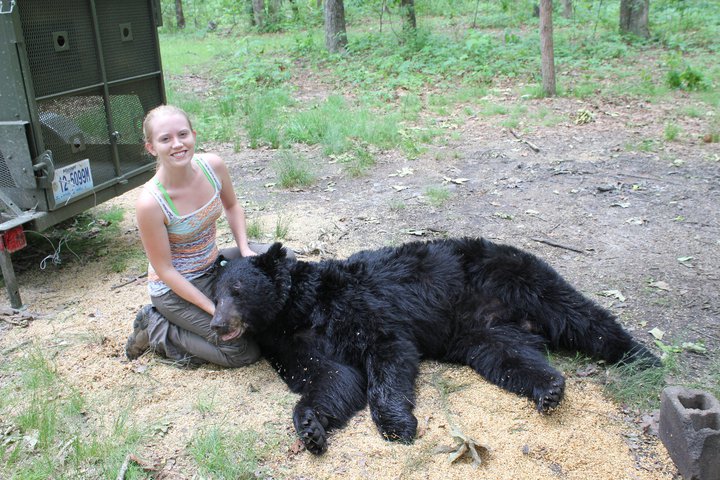

My bachelor’s degree is in Animal Science. I chose this major in part because I was interested in veterinary school. This was not the ideal major choice for me, however, because the biology coursework was lacking, and my interests eventually funneled into wildlife biology. I didn’t realize until the latter half of my degree that I wanted to study a different type of science, and so began my many internships and extra coursework in wildlife sciences. I went to Australia in 2008 for a study abroad program on wildlife medicine, and our classes on ocean conservation really ignited my interest in working in conservation research. This non-traditional background has been useful to my work as a wildlife biologist, however, in that my skills often fill particular niches (which roughly translates to me being able to handle a lot of species without injury as well as perform necropsies and assist in deliveries…though I wouldn’t ever try to help a bear give birth). I didn’t always know that my interests were meant for the field of wildlife biology, but I think my background is a good example of how veterinary medicine isn’t the only way to investigate animal systems.

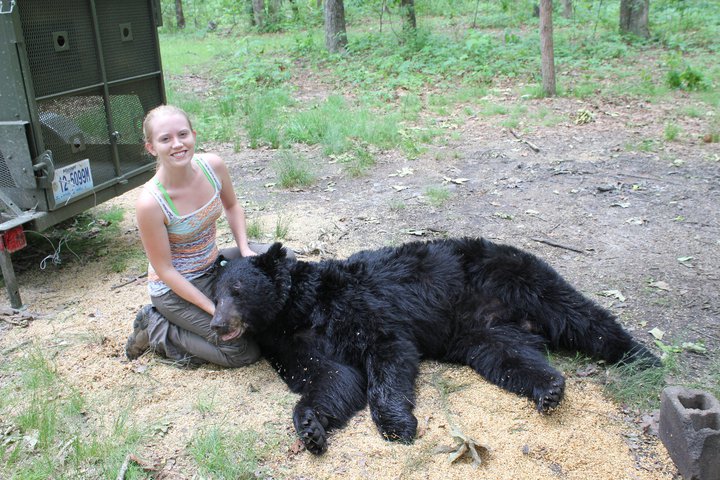

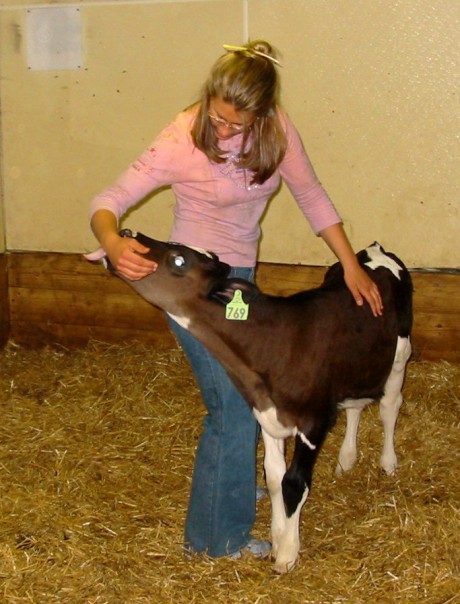

This bear was the biggest one I have ever seen. Helping the Missouri Black Bear Project take morphometric measurements includes overall body length, girth, tail length, leg length, even foot and toe length. Bears were also fitted with a radio collar for tracking purposes.

What was your first science-related job?

I did an internship at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences during my undergrad. I worked for the mammalogy department in the basement of the museum processing specimens and transcribing data files from the early 1900’s. It was a really cool gig because I got to cut up dead things (yes I really do enjoy that) and see firsthand how reporting data and disseminating research is useful to a variety of research efforts, no matter how old.

My first paid science-related job was right out of undergrad when I moved to northwest Montana to work on a bobcat ecology project. We were near Glacier National Park and I got paid to hike in remote back-country for several months collecting vegetation info, performing bobcat necropsies, and chasing radio-collared bobcats. To this day it remains the most fun I’ve ever had. I was regularly banged up and bruised up, but I worked with a phenomenal PhD student and developed a vast array of skills. We like to joke that it was a great summer because we didn’t get killed- we had a close encounter with a mama griz, almost fell off some cliffs, almost got swept away while crossing a river, and even got a teeny bit lost one day due to a compass malfunction (be sure to never have magnets on your gear if you are handling a compass in the middle of nowhere). Joking aside, it was a great project and a great experience. It is because of this position that I was offered all other research jobs.

Passing an anesthetized 007 to Mark.

What led you to get a Master’s Degree?

Obtaining my PhD in this field has been a long-term goal, so getting my master’s degree was part of the process. I didn’t feel qualified or prepared to jump straight into a PhD, and my master’s was a great introduction to creating and managing my own research. While not all areas of wildlife biology require a master’s degree or PhD, it is a competitive field and many positions regularly look for candidates with master’s degrees. However, there are many career options in this field where degrees above a B.S. are not required. Because I’m interested in wildlife research, getting a PhD is the most practical way to eventually have my own research program. I’m interested in landscape genetics, spatial ecology, and population connectivity, which means I’ll be looking for degree programs focusing on conservation biology, ecology and evolution, etc. On a personal level, I just want to be the best at whatever I do, and higher education is an avenue I’ve chosen to help accomplish that. I’m also totally nerdy and I love college! I would go to classes forever if they let me.

I received my master’s degree in wildlife biology at West Texas A&M University

Has your work allowed you to travel? If so, where have you gone and what were you doing there?

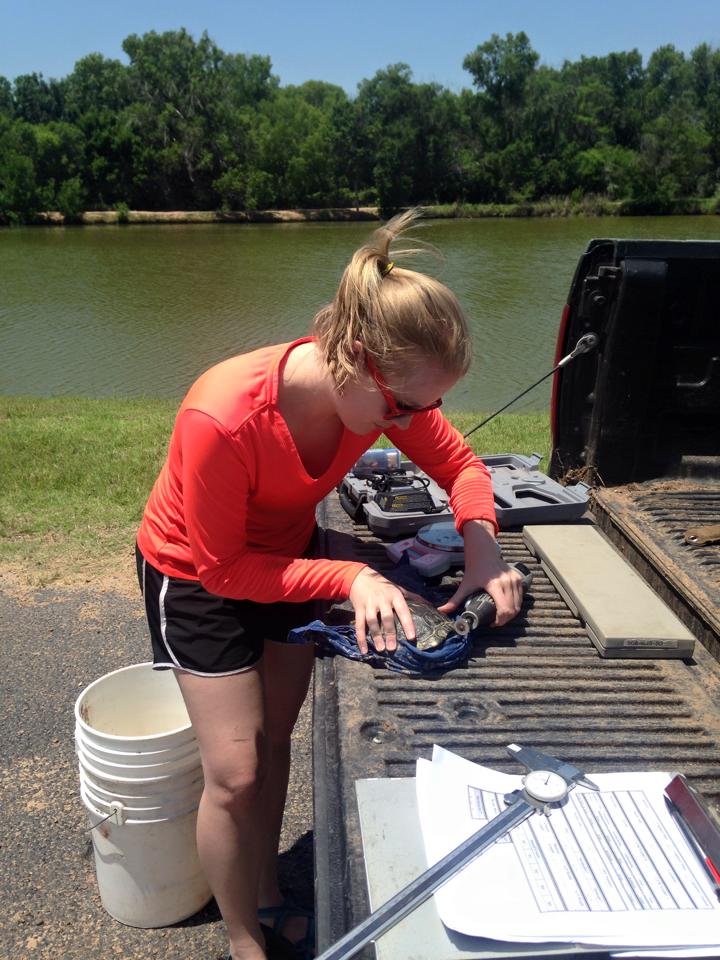

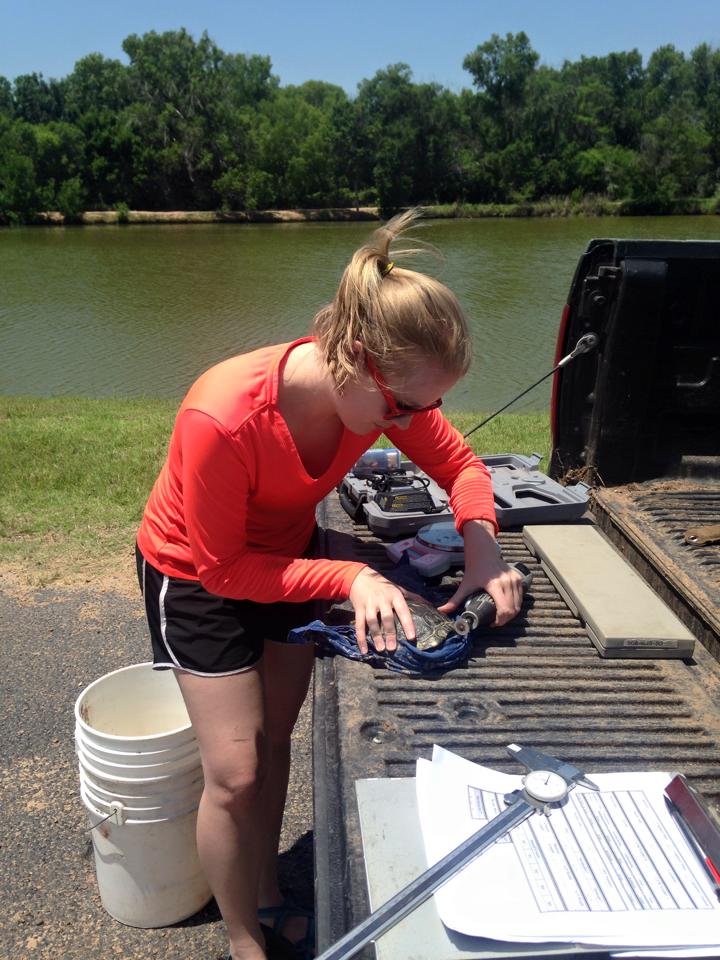

Yes! I have been fortunate to join research efforts across the US. I’ve worked in Montana, California, Washington, Missouri, Texas, Virginia, and South Carolina on various research projects. Before starting my master’s degree these positions involved field research, where I primarily worked gathering, monitoring, and/or processing biological data for different wildlife research projects. These efforts involved live-trapping and handling of bobcat and bears, collecting DNA samples from foxes, wolverine, fishers, and martens, studying reproductive hormones in the clouded leopard, and managing camera traps for wildlife studies. In graduate school I was also able to participate in a lot of research efforts outside of my own, and I’ve worked in several areas of Texas on various lizard, snake, and fish monitoring projects. My current research position in South Carolina gets me into the field to work with salamanders, so I’ve been fortunate to travel to a lot of places and see a lot of things. My personal favorites were working outside of Glacier National Park and in the Sierra Nevada of California.

Mole salamanders are stout salamanders with large, flattened heads. This Ambystomatid species is found throughout the coastal plains of the southeast US.

Can you share with us about your experiences working in different sectors such as academia, industry, non-profit, eco-tourism, citizen science, contracting, small business, or entrepreneurship?

I’ve mostly worked for academic institutions and federal agencies, including various universities, the US Forest Service, and the Smithsonian. I have enjoyed both avenues immensely because there is a heavy focus on the quality of research and the importance of disseminating that information to both the scientific community as well as to the public. Of course, the sector you choose to work in depends on your interests- I am interested in research as well as education, and fortunately for me that creates some flexibility. I currently work in social media to educate the public about nature- I think this is necessary for biologists. I also have friends who have done important conservation work in the private business sector, which shows that there are many opportunities in this field.

Holding a five-year-old 6-foot eastern indigo snake. These nonvenomous snakes are a threatened species that range throughout the eastern United States and prefer woodland habitat with burrows and debris piles. I showed this snake at a Boy Scouts event working with members of the West Texas A&M University chapter of The Wildlife Society focusing on wildlife education. Kudos to this ambassador snake for being very calm with so many Scouts wanting to learn about him.

Did you have any preconceived notions about science, or scientists, and did that change once you explored your career in science?

When I was younger I assumed that you have to be a bit of an antisocial genius in order to be a scientist. Aren’t scientists on screen and in books often portrayed as insular, peculiar, and a bit lofty? When I was younger I assumed that I couldn’t be a scientist because math scared me and because I love talking to people. Sometimes I still freeze up when it comes to numbers, but that hasn’t hindered my career in science at all. Also, many of the biologists I know are the most social butterflies of all! There is nothing more enjoyable than having a beer and talking science- really, that’s what a lot of scientists do! I know a few geniuses of course, but you don’t have to be dry and unyielding to be a scientist. Scientists aren’t scary or boring at all- some of the coolest people I know are biologists!

What were, or currently are, some big compromises or struggles you’ve experienced making a career for yourself in the science world?

Realistically, finding a permanent position that pays the bills has been the hardest part as a new graduate. For many, getting a master’s degree is necessary in order to make money in this field (though certainly not for all, and not always a requirement). Many wildlife science-related positions are in more remote areas of the country, which means that compromise is often necessary in terms of making life decisions. Finding balance is not impossible, but it is challenging, particularly when career interests funnel your options.

Now that I’m a little older, I’m not immune to issues that a woman in science might face. I have previously experienced inequality in the workplace (I spent an entire summer on a field research crew where I was the only woman), and while it certainly didn’t hold me back, dealing with issues such as salary inequality and sometimes the blatant sexism women can experience in the science world is both astounding as well as frustrating. My gender doesn’t cross my mind as a factor regarding my qualifications, so the notion that I could struggle in this field because I’m a woman is a little foreign and a little funny to me, but it’s not something that I totally ignore because it happens. If the time comes when I decide to start a family, it may involve compromise that I wouldn’t have to deal with if I were a man. I’m not there yet, but I have no intentions of letting that happen. I love science and I’m good at it, and at the end of the day that’s what drives us.

What keeps you motivated when you’re feeling the drudgery? What keeps science FUN for you?

I can’t imagine not having a job where I get to go outside and see things, find things, or explore. I do spend a lot of time in a research lab working with genetic samples, though, and even though I love it, sometimes you need a change of pace. Nothing rejuvenates me like getting my hands dirty or my heart rate up, and for me that usually involves field work or recreational time outside, like hiking. When I’m hiked out, I turn to painting (I paint wildlife and landscapes). For me, however, science is the most fun when you can share it- I really enjoy doing education programs for children and adults on wildlife and conservation. I’m also very active on social media- I post “facts of the day” on Instagram about wildlife I’ve encountered or worked with. It both reminds me why I’m interested in this field as well as satisfies my goal of getting others involved in nature. I’ll be launching a wildlife-themed podcast next month with a colleague. It’s called The Radio Collar- be sure to look out for it!

What do you want to achieve in your career? What is your big dream?

I plan to complete a PhD in the areas of conservation biology and ecology. My research interests are mediated by the desire to conserve biodiversity as well as study landscape connectivity regarding natural resource problems in conservation biology. I want to use my skills in a position that expects me to conduct quality wildlife research as well as works to engage the public. I specifically want to use my education to teach people how important and finite our natural resources are, including wildlife and natural habitat. My big dream is to work with an organization like National Geographic creating media that inspires and fascinates us to participate in conservation.

What are some key points you wish you knew or that you remind yourself of during your science career journey?

I absolutely love what I do, but it’s easy to get caught up in the rat race of it all if you aren’t careful! I shouldn’t have worried so much about the end game between my bachelor’s and master’s degree. I worried a lot about getting into a funded graduate program (I did), and getting jobs that would help me along the way (I did), and meeting the right people and making the right choices for my career (I did). Science is a serious field, and requires a certain mindset and a specific dedication, but nothing in life is about the end game. All of these things would still have occurred with just a little less stress on my part, and you better believe I wish I was still doing contract field jobs out in the middle of nowhere. You can’t always be serious. And you shouldn’t be! In a serious field that can involve a lot of pressure from grant applications, publication expectations, and research quality, it’s good to remember that it’s not actually work- it’s a passion.

Making sure to take it easy from the pressure of the rat race with stress reduction techniques. Gotta keep that passion stoked for the long haul!

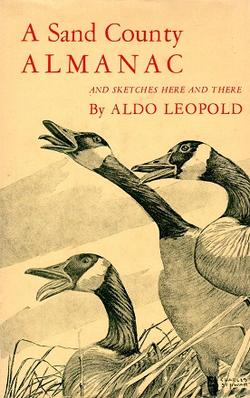

What are some inspirational materials you’ve used along the way?

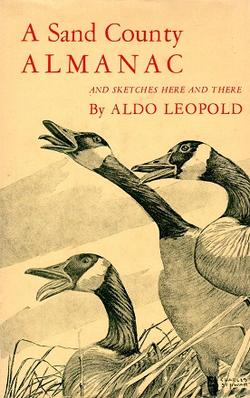

I highly recommend that everyone interested in wildlife, natural resources, and any other field of biology read “A Sand County Almanac” by Aldo Leopold. Leopold is considered the father of wildlife management. This text introduces the idea of the Land Ethic, which much of wildlife an natural resource management is based on. It’s not a dry text- it’s an easy read that connects you to nature through stories of skunks, the beauty of melting snow, and the complexity of songbird breeding season. Every outdoor enthusiast should read this book.

I also get a lot of emails from high school-age students seeking advice on how to get involved in the field of wildlife biology, and one of the tools I suggest is the Texas A&M University wildlife job board. This source posts research positions, internships, and education opportunities for all skill levels across the country and is a great way to fine-tune your goals. If you find a job that sounds interesting, you can review the qualifications needed for that position and work towards meeting specific goals.

Anything else you’d like to add?

The best advice I can give to those interested in a career in wildlife biology is to get involved ASAP. So many students think that good grades are the best way to get a job, but that just isn’t true. Good grades are essential, but so are real-world skills and experiences. Getting involved with research early is so important, as field skills and familiarity with the scientific process determine your eligibility for those cool jobs. Going to research conferences, being active in your wildlife society, and building relationships are also important in this field. Lastly, most wildlife biologists study many taxa instead of just one species-this field is about ecosystem/ habitat management and conservation, which means you focus on many different areas. That’s what makes it so fun!

-

-

-

Anesthetized gray fox in Palo Duro Canyon State Park. Citizen contribution enables me to understand how the landscape structures gene flow in gray foxes, coyotes, and bobcats.

-

-

-

-

-

-

marbled salamanders from pitfall traps.

-

-

A lovely coachwhip (Masticofis flagellum) I caught down in central Texas last week. Isn’t he gorgeous? More pics soon from my trip down to Independence Creek Preserve

-

-

Very fortunate to have interacted with a bobcat kitten, and even better that we were able to safely return him to his den.

-

-

The praying mantis is by far my favorite invertebrate- I’ve been fascinated with this insect since I was a child.

I’m so excited and thankful to be interviewed by Woman Scientist! Women in science fields form a really tight knit group, and I’m proud to be in a career that is supportive as well as full of brilliant, kind, and funny humans.

Thank you Imogene!

Want more photos? Check out the album on the Woman Scientist Facebook page.

And be sure to follow her:

Updates:

Imogene recently received the 2016 Clarence Cottam Award at the Texas Chapter of the Wildlife Society’s annual conference for presenting her work on the importance of spatial scale in landscape-mediated genetic structure. Her talk was titled, “Scale-dependent landscape genetics of bobcats across western Texas.” This award is given to recognize and promote outstanding student research.

Imogene recently started research at University of Delaware, in collaboration with Panthera, to complete PhD research on snow leopards.

Updated September 10, 2016

Congratulations and keep up the good work!

Share this:

by

by

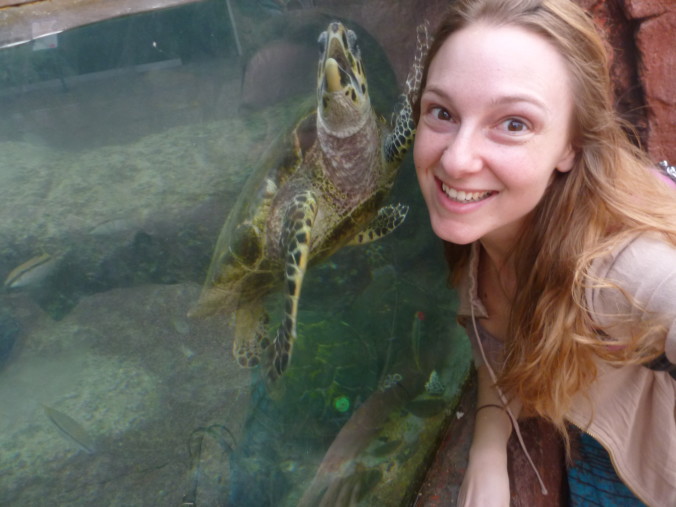

Upper: Sorting fish caught in a trawl on the R/V Centennial. Friday Harbor Laboratories, WAl; Lower: Snorkeling in American Samoa

Upper: Sorting fish caught in a trawl on the R/V Centennial. Friday Harbor Laboratories, WAl; Lower: Snorkeling in American Samoa