Welcome to Field Diaries – Reflections of Life in the Field

Field diaries, or subjective reflections, are just as informative and useful as objective research field notes and serve as an important avenue in outreach connecting scientists and science to the public.

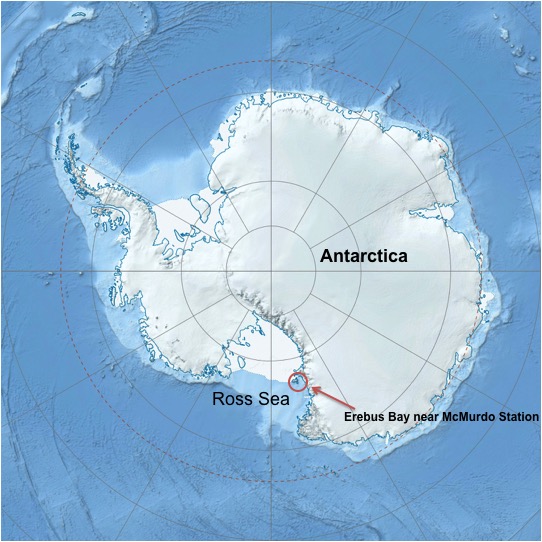

This week Woman Scientist is featuring anecdotes about field life from the perspectives of Kaitlin Macdonald and Erika Nunlist, two team members with the Weddell Seal Population Study (2015) based out of Erebus Bay, Antarctica.

Kaitlin Macdonald is a current M.S. student at Montana State University and has worked on research projects since 2012. She joined the Weddell seal project in 2014 and is now in her 2nd year being advised by Jay Rotella, Robert Garrott and the project’s co-leader with Terrill Paterson for the field crew. She holds a B.A. in Environmental Studies, a B.S. in Economics and has also done field work with mountain ungulates and small mammals..

Erika Nunlist graduated in 2015 from Montana State University with a B.S. in Conservation Biology & Ecology and a Minor in GIS. She has worked as a wildlife technician on Sandhill cranes, Long-billed curlews, small mammals, mountain goats, and sage grouse and is exceptionally excited for her first year on ‘the ice’ researching Weddell seals.

The Ross Sea is one of the few pristine marine environments remaining on this planet. One of the most productive areas of the Southern Ocean is located in Erebus Bay and hosts the most southernly population of breeding mammals in the world, the Weddell seal. Over 20,586 marked individuals have been intensively studied since 1968 and provide an excellent opportunity to study the links between environmental conditions and demographic processes in the Antarctic.

The Weddell Seal Field Team has a huge job during the busy pupping season. Crew members work long days, traveling far and wide over the sea ice looking for seals. Researchers tag, weigh and re-weigh pups and adult seals as well as take genetic samples for analysis back in the lab.

To put the season in perspective here are a few statistics from Kaitlin:

- Set 18 miles of flagged road on the sea ice.

- Tagged over 650 Weddell seal pups in our study area.

- Tagged 6 pups at White Island.

- Enrolled 173 pups in the mass study.

- Weighed a total of 69,708 lbs. worth of pups.

- Deployed and collected 122 temperature logging tags.

- Counted 1,444 tagged animals in our largest survey.

- Have photogrammetry mass assessment projects for

40 Weddell females.

Luckily for us, the scientists sneak extra time out of their busy day to capture photographs and videos which document the research and their experiences.

We begin this Field Diaries Series 1 with an entry from Kaitlin Macdonald.

Enjoy!

If you would like to help support this project, head on over to their campaign on Experiment! They only have 10 days left to reach their goal!

Dec. 8, 2015

Howdy!

Well this is my first and probably only update from Antarctica. We have had a hell of a season so far and we still have a week left. I had the honor of helping the PhD student on the project Terrill lead the best Antarctic crew to date. Photo courtesy of our advisor Jay who came down with the other PI on the project Bob to help us tag pups for a few weeks.

I guess we will start at the beginning. We were pretty lucky with flights to the ice, we were only delayed 1 day in New Zealand and we arrived on a beautiful clear evening.

We were in McMurdo for the first week going through trainings compiling gear and preparing for our field season. Last year I was in bed well before the sun would dip down to the horizon, this year I was able to see a few sunsets before the sun stopped dropping down to the horizon. Pictured below is the Royal Society Range.

One of our trainings was crevasse rescue. We do this training because we have aggregations of seals on either side of the base of the Erebus Glacier tongue. This is a weird grey area for us to travel in, it’s technically not glacier but it is an area that doesn’t break out with the sea ice resulting in larger cracks and is more prone to calving and ice falls. We do the training as an extra precaution for entering this area. In our training pictured below we had to pull our instructor out of a crevasse he had rappelled into earlier, using a pulley system and snow anchors.

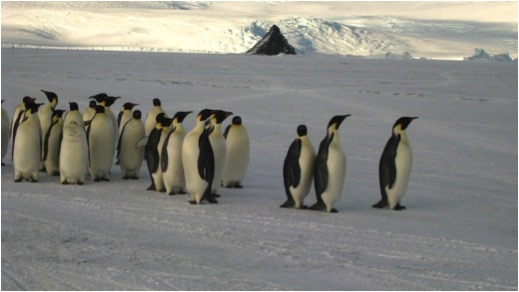

Early in the season there were large congregations of seals at the ice edge. We spent an afternoon surveying these seals to make sure there were not a large number of females with pups we were missing. While we were at the ice edge we saw a storm petrel fishing and a group of emperor penguins swimming along the edge. They look surprisingly like loons in the water.

This year we have seen many more penguins around camp, it seems this might be due to the ice edge being much closer. These guys were walking through camp one evening. We have started seeing snow petrels as well, which is quite exciting considering we didn’t see any last year.

We had such an incredible season. We had a record number of pups born and tagged in our study area. The old record was 608 and I think to date we have tagged 658. It is likely this spike in pup numbers could be a strong cohort of seals reaching reproductive age and having pups of their own. We have also weighed a record number of pups (69,708 lbs) and have had great success taking photos of moms, which is awesome news for my thesis!

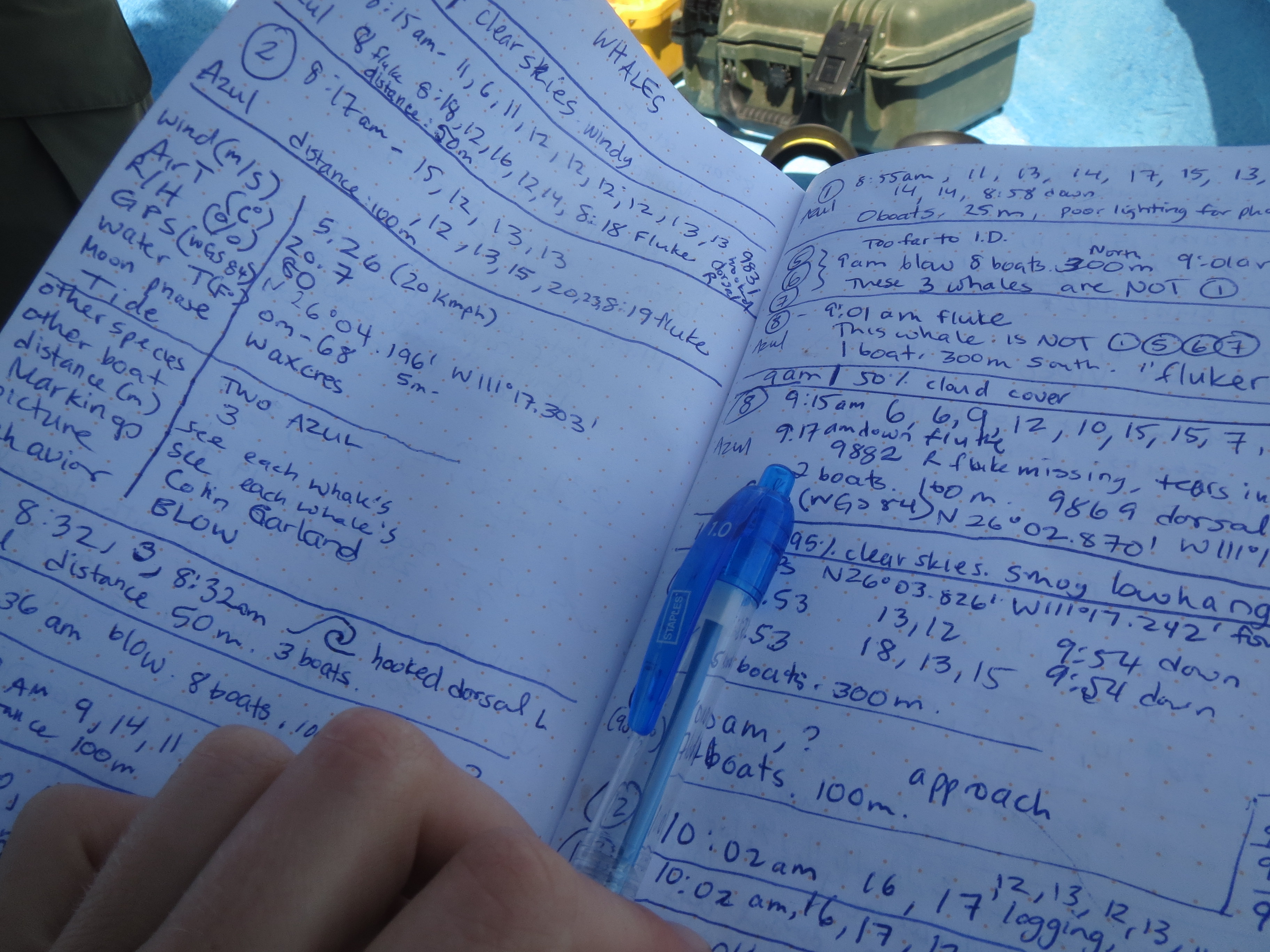

During the second half of our season we do surveys of our study area every 5 days. This involves checking tags of every seal you encounter writing them in a field notebook and inputting them in a hand held computer. This is no small feat when you have 1600 seals and 6 people. When you have co-workers like Erika who can survey with a smile it makes the task immensely easier.

The pups are rapidly transitioning from the awkward molting period, which I liken to middle school to fully molted and weaned. The little lady on the right had already made it out to the open water and was lounging in the pack ice.

Speaking of records, we may have come close to breaking a record number of snowmobiles this year. It is nearly unavoidable down here but for some reason welds on the frames and suspension were breaking quite often. When a sled breaks in the field we have to load it onto a Siglin sled and cargo strap it down before pulling it to town. This particular instance we were out of cargo straps and improvised with bungee cords!

We have been very busy wrapping up our season. We visited both colonies on the edge of the Erebus Glacier Tongue one last time to tag any pups we may have missed.

Mandatory glamour shot of the crew!

We also made a helicopter trip out to a population of seals that are trapped at White Island by the Ross Ice Shelf. The ice shelf broke out incredibly far sometime in the 1950’s. The distance from the ice edge to White Island was short enough for seals to colonize the Island. The ice froze again and has never broken out far enough for the seals to survive the swim to open ocean or a breathing hole in the sea ice. This population shows signs of inbreeding and is quite small. We tag animals and take genetic samples at White Island twice a year. We tagged this little guy and 2 other pups, which is a lot of pups for this time of year at White Island.

We have been reminded how soon our season is coming to an end by the rapidly warming temperatures. It has been above 30 degrees for the past week or so, with some days near 40 degrees. While it feels wonderful to only wear a baselayer under our jackets the sun has not been so kind to the sea ice. Slush pools and cracks are growing daily and our camp is slowly sinking into the ice. It isn’t too alarming as the ice is melting from the top so we still have 88 inches before we hit the ocean. It does make navigating camp difficult with calf deep puddles. We set-up a path of wood blocks around camp so you don’t have to risk getting your socks wet anytime you venture out your door. In this picture Eric and Mike are navigating around the largest pool which has formed outside of our gear hut.

Well folks that is all I have for you. Thank you for reading this far, I hope it gave a small glimpse into our lives down here. Our huts are being pulled today and then we spend the rest of the week packing, cleaning and returning our gear before taking off from the ice!

-Kaitlin Macdonald

All photos obtained under B-009, Permit number: 2013-007, NSF, Antarctica

Thanks for reading!

Be sure to catch the second post in our Field Diaries Series, coming tomorrow!

If you would like to help support this project, head on over to their campaign on Experiment! They only have 10 days left to reach their goal!

Share this:

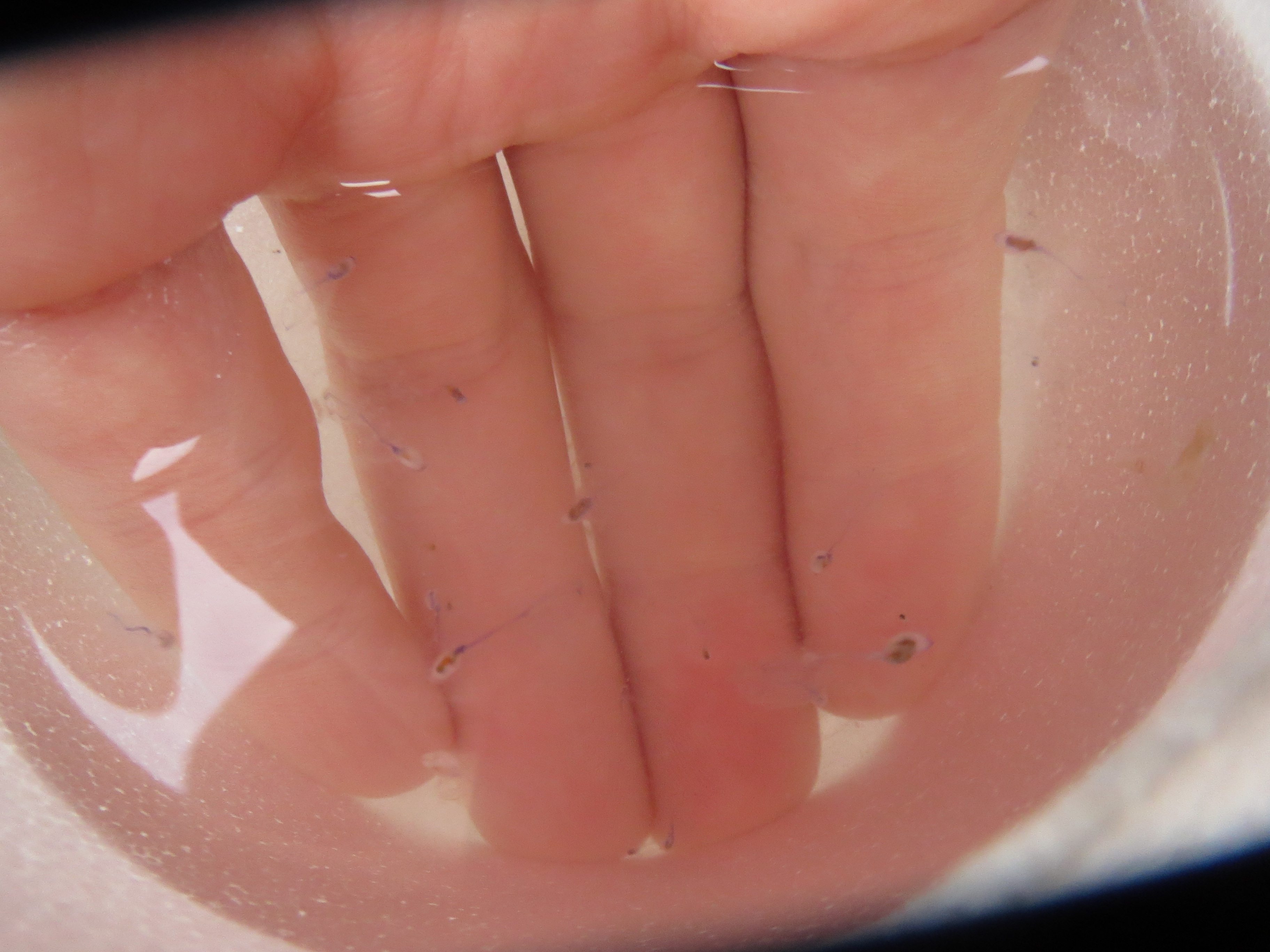

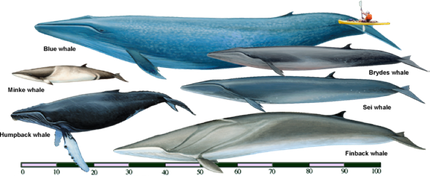

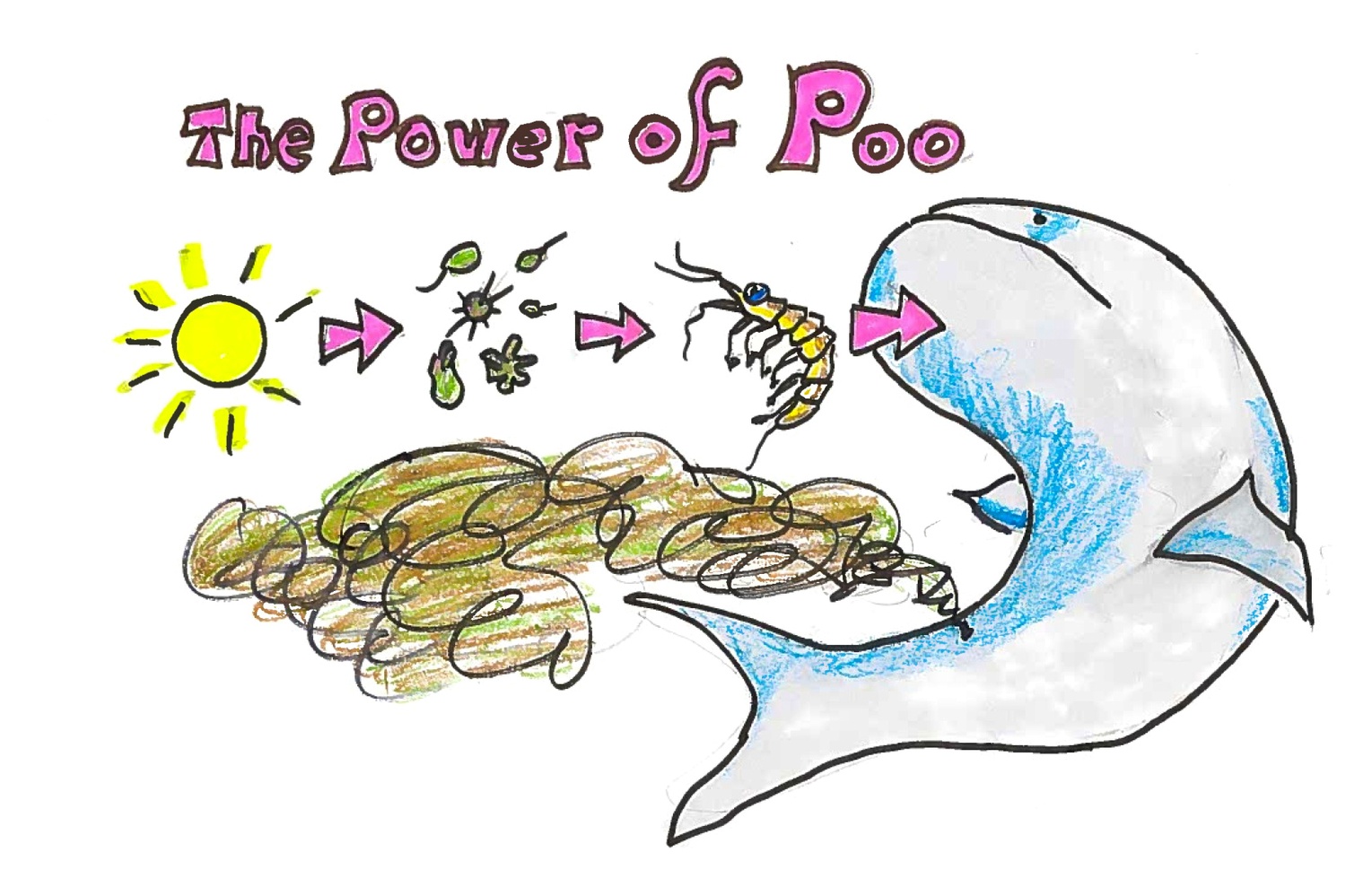

Magnificent Blue Whale pigmentation and the mouth of a Humpack Whale.

Magnificent Blue Whale pigmentation and the mouth of a Humpack Whale.