One day Lauren came over for a dinner where the discussion had turned to nerdy science topics, as most dinners with curious people do. We had a giant spread of butcher paper over the kitchen table and we turned to Lauren and asked her to share something nerdy with us.

Little did we expect she would be armed and ready for us; Off she went capturing our attention with explanations of the biology and evolution of jellies.

I distinctly remember making a mental note that often times people call them jellyfish when in fact they should just be referred to as “jellies”. From that day on, I always call them by their proper term.

Lauren is incredibly enthusiastic and passionate about her marine invertebrates from jellies, to nautilus, to all the vast array of deep sea creatures. She contradicts all stereotypes of scientists being dull and boring, which you can see immediately by her bright red hair and refreshingly quirky style. She is down to dress up and strut her stuff in every aspect of life blending friends, family, fun and science!

At the time of this posting Lauren is currently working her way through graduate school studying evolutionary marine biology. I wanted to capture this time in her life as she continues to carve her niche in her career. She has great perspective and solid advice for those of us figuring out our way in the life sciences, so without further adieu, I give you Ms. Lauren Vandepas.

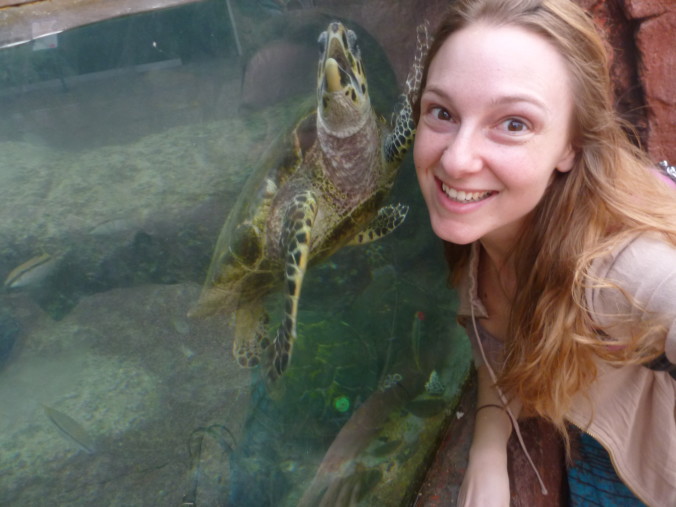

American Samoa, a few miles offshore. Taking pictures with a nautilus we caught before divers returned the nautilus to a depth about 70 feet and released it. We took tissue samples for DNA and RNA, weighed, measured, sexed, and x-rayed the nautiluses. Photo by Tom Tobin

1. What did you study during undergrad? Did you know at the time you wanted to study jellies and ctenophores?

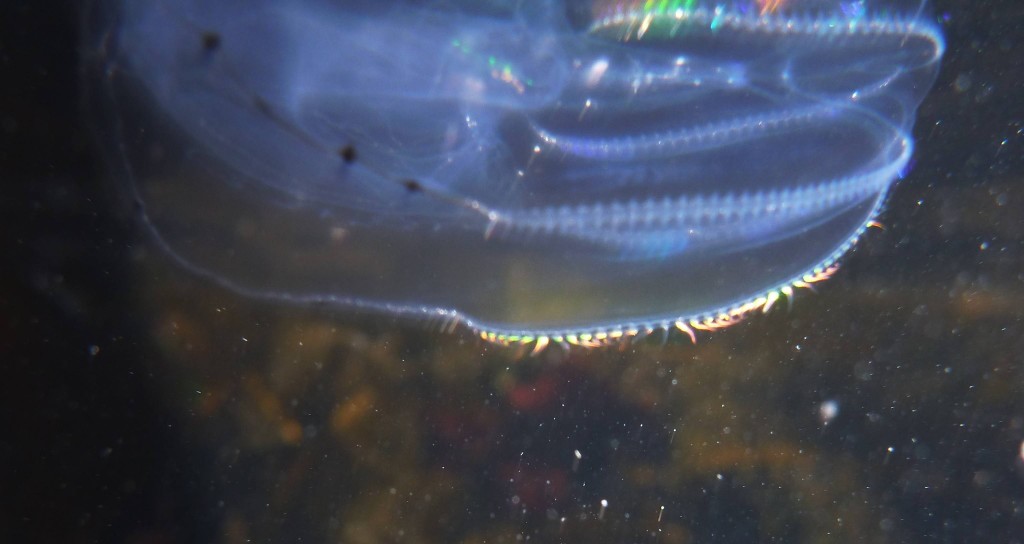

I double majored in Biology and Marine Science at the University of Miami with a minor in Chemistry. Deep sea animals and ecosystems were especially fascinating (we didn’t talk about them nearly enough in my classes!). I always loved jellies and thought that ctenophores were the most alien things I’d ever seen. I was interested in how these awesome animals evolved, why deep sea critters look so strange, and how animals make their own light.

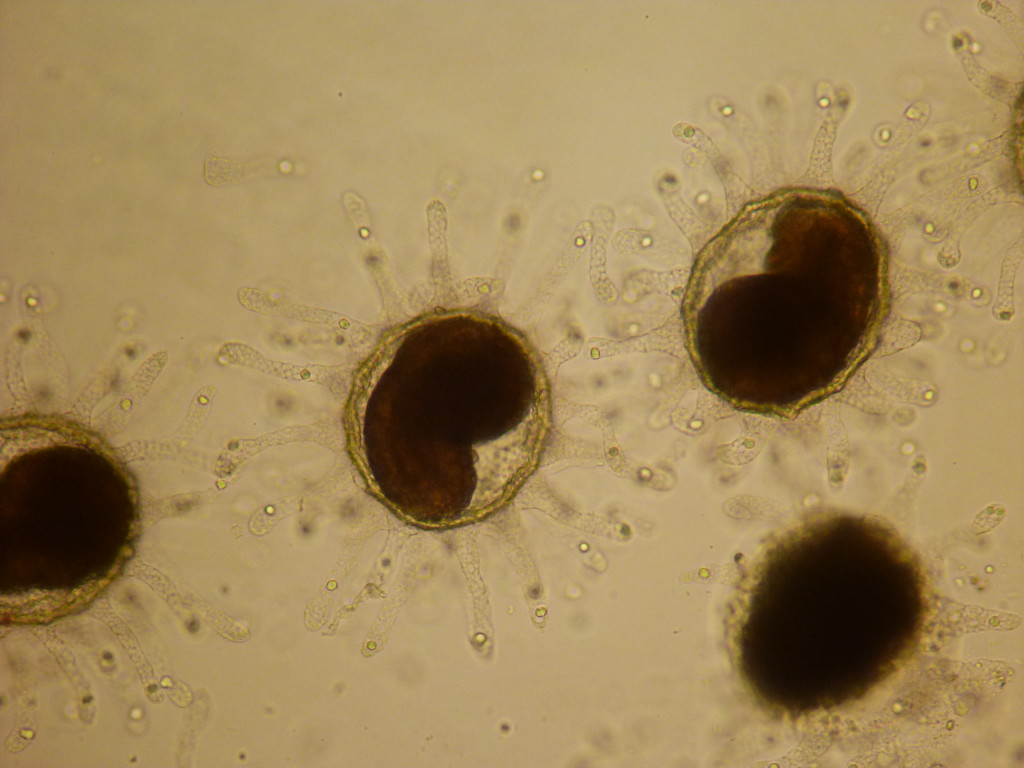

Developing tunicate tadpole larvae (Ciona) at the Misaki Marine Labs.

2. What type of job opportunities have you had over the years during college and after college?

When I was in college, I was eligible for a Federal Work-Study. That allowed me to get a paying job working in a coral research lab. The skills I learned there really helped with my job hunt after college. I graduated in 2008, when the economy was still “free-falling”, and I was living in a job market that was one of the hardest hit from the crash. It took me a year after graduating to find full time work in science. I was exploring research technician jobs at universities and colleges in my area, as well as looking into government jobs. I eventually got a position in a medical research lab. It initially bummed me out what I wasn’t able to find a job in marine science, but I learned so much by switching disciplines.

Doing something completely different allowed me to build on the skill set I had in genetic work and learn a ton of other techniques that I wouldn’t have necessarily been exposed to. My mentor, Dr. Suzy Bianco, was awesome and my time in her lab allowed me to become a stronger applicant for graduate school and a better scientist.

I was worried for a while that working in another field might reflect negatively on me down the road (not sticking with just one thing), but it turned out to be the opposite!

Bit of an aside… A lot of people end up volunteering in labs to get research experience, and it’s really critical to have that experience under your belt (one year commitment is minimum to get a lot of skills down) when applying for jobs post-undergrad or for graduate studies (med school, etc). So to anyone hoping to go into life sciences as a career, I’d highly recommend joining a lab during undergrad to get some experience!

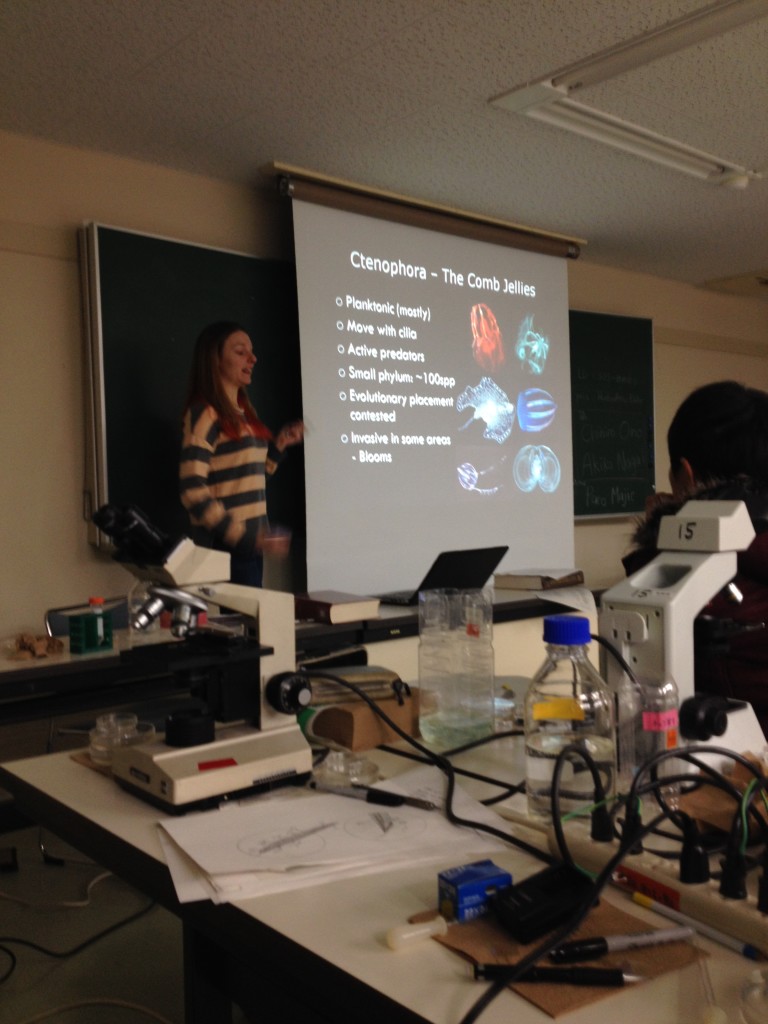

Lauren showing off Ctenophore wound healing assays at Friday Harbor Laboratories in the San Juan Islands.

3. Where have your studies and work taken you?

One of the awesome things about science as a career in general, and marine science in particular, is that there’s a lot of opportunity for travel. It’s one of the rewards of the job! There’s data to collect, collaborators to visit, conferences to attend, courses to take. Many universities (and marine laboratories) offer graduate-level courses for specific disciplines. Because there’s such a large international network of scientists in any field, a lot of conferences rotate between countries.

Here are some of the places where my studies have brought me, whether for collecting samples, having the chance to learn from others, or attending conferences:

- Bocas del Toro, Panama – I took a course on larval invertebrate (mostly plankton!) diversity, form and function at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute

- Pago Pago, American Samoa – I got to join collaborators on an expedition to collect nautilus. We used the tissue we obtained on a project examining the relationships of separate nautilus populations

- Eilat, Israel – The Coelenterate Biology meetings were held in Israel (“coelenterate” is a term that used to be more commonly used to describe comb jellies and cnidarians.).

- Misaki, Japan – As part of the E. S. Morse Institute (a scholarly exchange between marine biologists at the University of Washington and University of Tokyo). I attended an invertebrate embryology course at the University of Tokyo’s marine labs.

It’s been fantastic to be able to connect with and learn from scientists around the world, as well as see some amazing nature first hand (the Red Sea! the amazing diversity of Indo-Pacific coral reefs!).

4. What kind of scientist do you consider yourself?

Biology is a huge discipline! I think cases where scientists are completely encompassed in one field are pretty rare. Usually research is spread across several sub-disciplines and the science is under a few different headings simultaneously. Broadly, I would say I’m a marine biologist – I study marine invertebrates. But what do I study about them? I’m interested in why the life we see is so diverse in form and color. How did all of this biodiversity evolve? So I’m an evolutionary biologist, but the way I study evolution is to look at the development of different animal groups (which genes are involved, etc.).

Sharing research with other students at the Misaki Marine Labs

In the lab, x-ray of a live nautilus (the animals are unharmed during this process). Pago Pago, American Samoa

5. Did you have any preconceived notions about science, or scientists, and did that change once you explored your career in it or do some of them remain?

Originally, I thought there would be a lot more outdoor exposure. It turns out field work makes up a small amount of the actual time I spend doing science. A majority of the efforts are actually spent analyzing the samples or data collected in the field. Also, you get very, very attached to your set of pipettes.

One great thing about marine biology, and something that was always attractive to me, was that I didn’t associate working in this field with the (often negative) stereotypical image of a stuffy scientist in a lab coat working in a stuffy acrid-smelling lab. Although, I did make the lab smell pretty awful just the other day when I was working with chemicals. I mean, does β-Mercaptoethanol have any olfactory equivalent? Smelly chemicals aside, I’ve come to discover that science is not stuffy.

6. What led you to get a higher degree? How did you decide between staying at a Bachelor’s vs getting a Masters, or PhD?

I really wanted to be a scientist, as my career. I wanted to do research in marine science and after talking to people in the field and exploring job postings online, realized that to be able to have the career I wanted, I’d need a PhD.

7. What were/are some big compromises or struggles you’ve experienced trying to make a career for yourself in the science world?

One of the biggest struggles that I’ve faced and witnessed friends deal with is balancing a career in science while still paying attention to other aspects of life (family, hobbies, friends). There’s a perception that if you’re going to be a successful scientist, you have to work 80 hours per week, to the detriment of spouses, family, health…

It seems like that paradigm may be slowly changing and that there’s a pretty recent, more active, conversation about work-life balance. There are many articles on the subject by people who are way more eloquent than I! I think that’s probably the largest functional challenge I have made or will have to make.

It’s something that I’m still struggling with and thinking about as I look to what my career might be like after I finish my PhD. Doing research is so satisfying, challenging, fun, and often dirty/salty/muddy (in short, awesome), and I’m not sure I’d be happy in another field. However, I don’t want the work to make up 100% of my day-to-day either. Everyone deals with it differently and I haven’t figured out what the best path forward for me would be yet.

8. Did you get hooked by science immediately or was in more of a natural progression?

I grew up in South Florida and we have some awesome nature there. Coral reefs! The Everglades! Mangroves!

Spending time in this environment and exploring was such a joyful and comforting experience that I wanted to figure out a way to be around and think about the ocean all the time. I took advanced science classes whenever I could in school and was fortunate enough to have parents and family who signed me up for marine biology summer camps or took me to the beach, or snorkeling, or tide-pooling. I’ve always wanted to remain immersed in this field, and if I can even get paid to do it, hot damn!

9. What keeps you motivated when you’re feeling the drudgery? What keeps science FUN for you?

I go outside! I head to the rocky intertidal here in Seattle, or make a point to go snorkeling when I visit my family in Florida.

Volunteering and outreach really keeps things fun, too. Working with kids and the public, I remember why I’m so jazzed about plankton and volcanoes and all things science. I get re-energized showing others how awesome our world is. Having a 2nd grader exclaim, “THAT’S SO COOL!” at a big green isopod you just handed them is a real pick-me-up.

Upper: Sorting fish caught in a trawl on the R/V Centennial. Friday Harbor Laboratories, WAl; Lower: Snorkeling in American Samoa

Upper: Sorting fish caught in a trawl on the R/V Centennial. Friday Harbor Laboratories, WAl; Lower: Snorkeling in American Samoa

10. Advice you would tell youngsters; Some key points you wish you knew before you set out.

This is going to sound hugely cliché, but… do what makes you happy. If science classes are your favorite, keep at it! Don’t let anyone tell you it’s too hard or there’s MATH or that you have to have perfect standardized test scores. There are a lot of opportunities out there at any level (bachelor’s degrees, PhDs, whatever!) to do what makes you happy.

No one goes into this field for the money, it’s not exactly the most well paying gig, but I do science because I love it and wouldn’t be as satisfied with any other career.

Want more?

Make sure you check out more photos from Lauren’s scientific adventures in the Woman Scientist Facebook album.

All photos courtesy of Lauren Vandepas.