(This blog was originally written for the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators Blog here).

As you plan your trip to Antarctica you dream of seeing the ice, the whiteness, the dramatic landscape, the penguins, whales, and seals. You pack your camera and imagine the wind biting your cheeks, wondering how it’ll feel to be in one of the most extreme environments on Earth. You’ll be amazed to see how these tiny penguins withstand such harsh winds, below freezing temperatures, and dark cold nights. You’ll feel giddy when you see a seal blubber along an ice flow or slip gracefully into the water. You’ll shout for joy when you see large baleen whales lunge feeding on a swarm of krill at the ocean’s surface. And you will be even more amazed, when you learn about, and see with your own eyes, what makes this whole ecosystem come alive.

But for that surprise, you will have needed to pack a microscope. And prior to your trip, you most likely will not be dreaming of this peculiar set of organisms that give life to a seemingly inhospitable place.

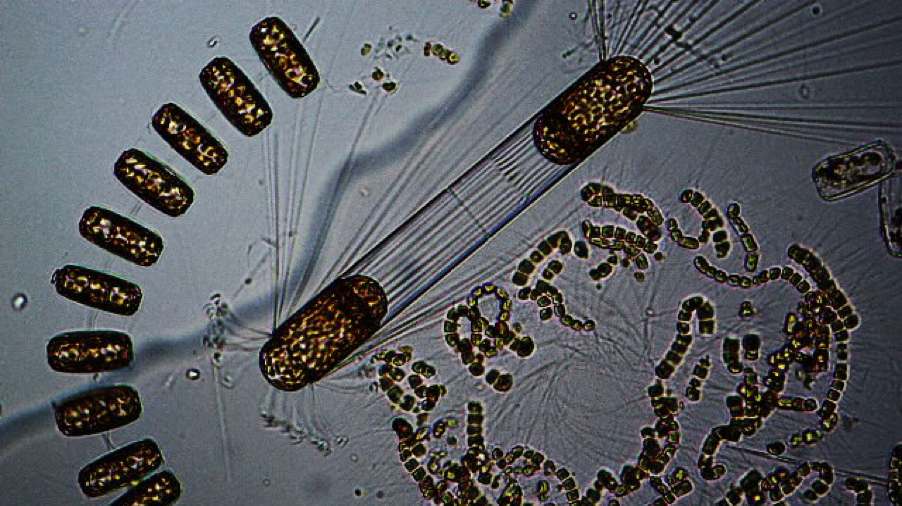

Within the crystal aquamarine waters of Antarctica lie tiny little organisms you cannot see with the naked eye. They are like plants – in that they use sunlight and carbon dioxide to make energy through photosynthesis – yet, they’re not plants. They are also not bacteria, nor fungi, nor animal. They belong to a group of organisms called protists; mysterious otherworldly life that has had millions of years to evolve.

Biologists call these little solar panels adrift in the ocean ‘phytoplankton’, stemming from two Greek words phyton or ‘plant’ and planktos or ‘wanderer, drifter’. Each type of phytoplankton is only one single cell – just one. Humans are made up of trillions of cells. And each single phytoplankton cell, when growing in massive groups called blooms, collectively produce over 50 per cent of Earth’s oxygen; just as much, if not more, than the plants and trees on land combined.

They draw carbon dioxide out of the ocean and atmosphere and upon death sink to the sea floor below, cycling carbon around the globe. These microscopic life forms also make up the foundation of food for all marine life to survive—the life of those same large charismatic animals you’ve come to Antarctica to see – and the life living on the sea floor; they all depend on the presence of phytoplankton for their survival.

The Antarctic Peninsula is the fastest warming region in the Southern Hemisphere, with air and ocean temperatures increasing, causing sea ice and glaciers to melt at accelerated levels. When glaciers melt, this brings freshwater to the ocean and alters the physical and chemical nature of the marine environment. With warmer temperatures, the surface of the sea cannot freeze into a skin of sea ice, which provides a protective habitat for Antarctica’s dominant keystone animal, krill. Baleen whales, seals, and penguins eat krill, their breeding success depends on it, and krill depend on sea ice and phytoplankton to survive.

All the breeding cycles of Antarctic animals – from big to small — occur in synchrony and follow in succession with the spring phytoplankton blooms that come after winter’s end. These marine ecosystems have developed over millions of years and adapted to natural seasonal fluctuations and climate variability, but current rising temperatures of today, caused by human sources of carbon emissions, will test the limits of these systems beyond what their natural variations have predetermined. At what point will we tip the scale and yet again alter the Antarctic marine environment as we know it?

With this complex layered dance going on, it would be wise to pay attention to how phytoplankton – the krill food – changes during a season. Just like the harvest for produce changes during certain months of the year, not all phytoplankton types exist in the same months. Not much is known specifically about what happens to phytoplankton throughout an entire summer season because research funding and monitoring at this fine time scale has been limited, leaving Antarctica a relatively data-poor region of the world.

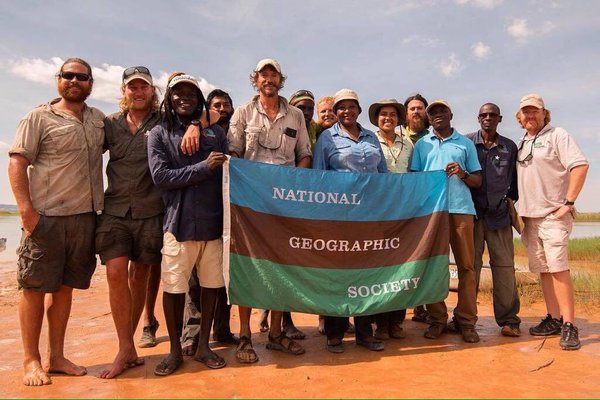

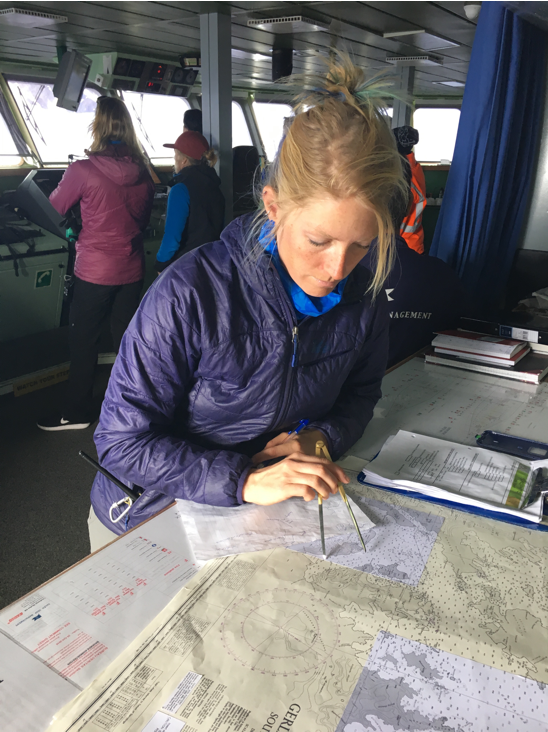

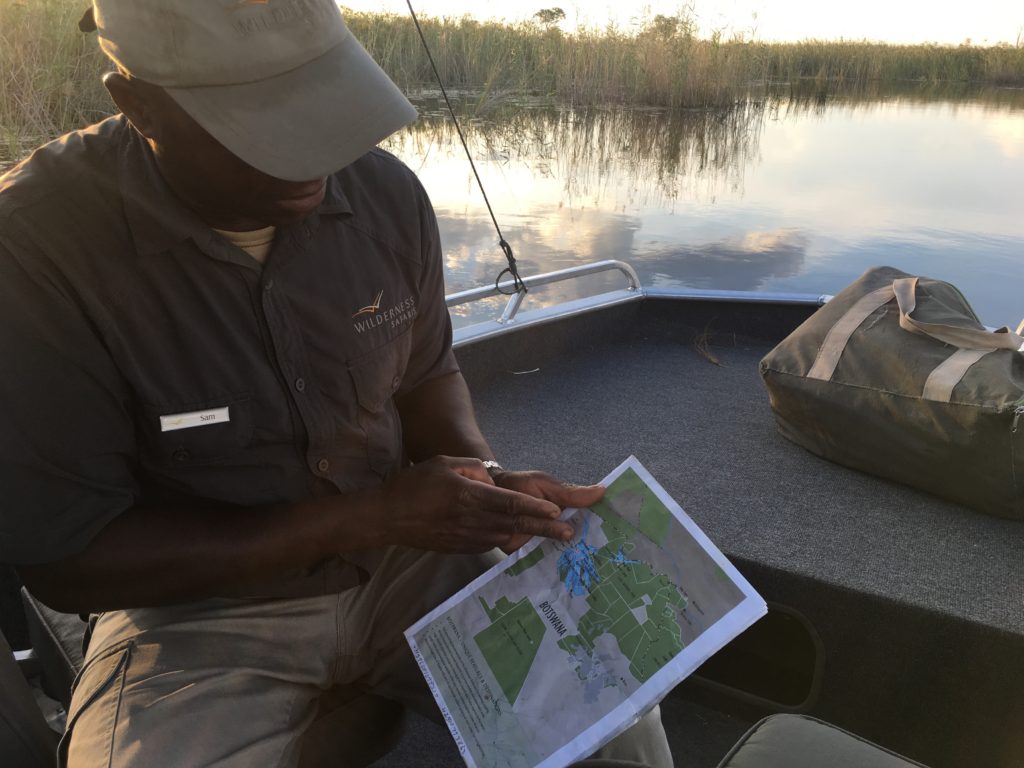

Tackling this challenge to learn more about a data-limited region, is exactly what motivates scientists like me to dedicate my career to solving these mysteries. With researchers in the Vernet Lab at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, we are looking in to these patterns. Every season since 2016, the citizen science project FjordPhyto has partnered with multiple vessels that are members of the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO). Each time a ship explores a specific location along the Antarctic coast, travelers hop into a dedicated science boat to help collect samples for science.

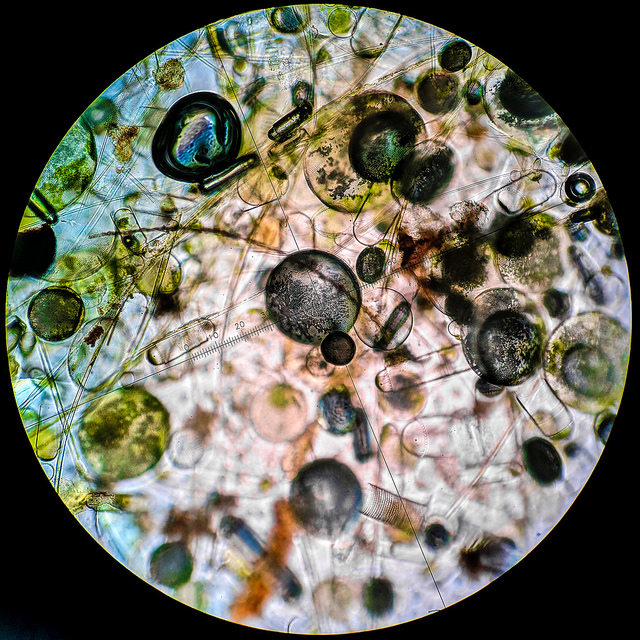

With the assistance of trained guides, travelers concentrate phytoplankton using a net to strain out the seawater. They filter the sample onto a membrane and preserve it for analysis by us researchers back in the lab at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and University Nacional de la Plata in Argentina. We will look under high powered microscopes to identify species, and pair that information with analysis using genetic tools to look in more depth at their role in the ecosystem.

These samples provide data to two PhD student’s dissertation theses: my own at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego California, USA, and Martina Mascioni at Universidad de la Plata in Argentina (SCAR and IAATO Fellowship recipient).

With many ships collecting multiple observations at many locations over time, we can start to look at changes in phytoplankton throughout the season and learn even more about the seasonal cycles of growth. After analyzing samples collected by citizen scientists from our first season of FjordPhyto, we published the project’s first scientific article, Phytoplankton composition and bloom formation in unexplored nearshore waters of the western Antarctic Peninsula , by Mascioni et al. (2019). If we can link how the base of the food web – the phytoplankton communities – shift in relation to their changing environment, we might be able to predict how krill and the larger animals will respond.

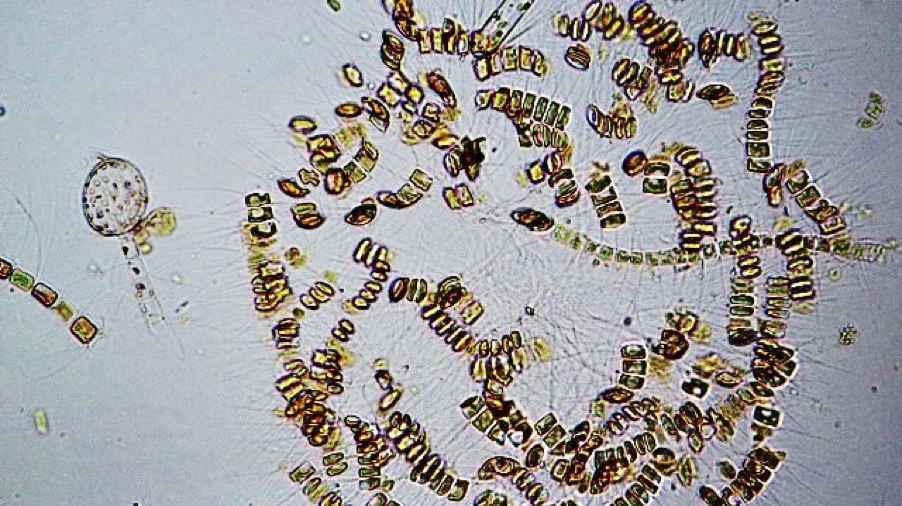

After travelers collect samples with FjordPhyto, they bring it back on board for a viewing session under microscopes. That’s when the fascination and amazement begins in trying to imagine how these individual single cells, floating in front of your very eyes, live in a bigger community with many millions more cells, and can have a huge global impact on the environment. You may be familiar with phytoplankton in your daily life through experiencing the sight of bioluminescent waves crashing on a beach, through harmful algal blooms like red tide, that produce toxic compounds leading to shellfish poisoning and fish die offs. When the waters turn discolored or cloudy greenish brown this is typically a sign of abundant phytoplankton in the water.

Some algae are also being used for biofuel potential and as a superfood to enhanced health (for example, spirulina and cyanobacteria, a blue green algae). In this way, you have always been aware of their existence. But not until you see them up close, after collecting them from seawater yourself, does the experience and connection become so much more impressive.

Although phytoplankton are one of the simplest forms of life, there is a huge diversity among them. They come in all shapes and sizes and number in the hundreds of thousands of species. Many can be grouped into broader categories.

If you feel comfortable naming star constellations, various birds, or varieties of flowers, then naming a few of the phytoplankton groups shouldn’t scare you off too much. These larger groups include some that are covered in silica – a glass-like material – called diatoms, some use calcium carbonate like chalk, such as coccolithophores, and others are made of cellulose like wood, such as dinoflagellates. There are also the red algae, green algae, cyanobacteria, and small flagellates, just to name a few.

They have a crazy evolutionary history starting back 2.7 billion years ago – when the first solar powered single cell (cyanobacteria) first existed. These blue green algae were engulfed by another type of single cell, becoming one and giving rise to red algae and green algae. Green algae then gave rise to land plants 470 million years ago. And both green and red algae were engulfed again multiple times to give rise to variety of protists we see today.

Understanding these organisms at the genetic level can get complicated. Their genetic code ranges from small to massive, some have a genetic code that is 100 times larger than the humans! You have to wonder, what do they need all that DNA for? If you like sci-fi, aliens, and space, its near impossible to not find phytoplankton mesmerizing, captivating the imagination.

So next time you’re looking out at the vast blue waters and wonder why a place is rich or devoid in life, the presence or absence of the big animals you know and love, think at the level of microscopic. Think about the dramas playing out in the world of tiny organisms fighting for survival. Everything else you can see with your naked eye, appreciate that it’s supported by the first level of life, the phytoplankton, Antarctica’s gold.

After your trip, you just might find yourself dreaming of learning more about these peculiar lives that give abundant life to one of the most extreme places on Earth. And next time you pack your bags, you just might leave room for a travel microscope.

About the author | Allison Cusick

Allison Cusick is a graduate student (PhD) studying polar biological oceanography in the Vernet Lab at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, California. Since 2017, she has been traveling annually to the Antarctic Peninsula through her graduate work running the Fjord Phyto citizen science project, collecting samples, and giving lectures to guests on-board various expedition ships.

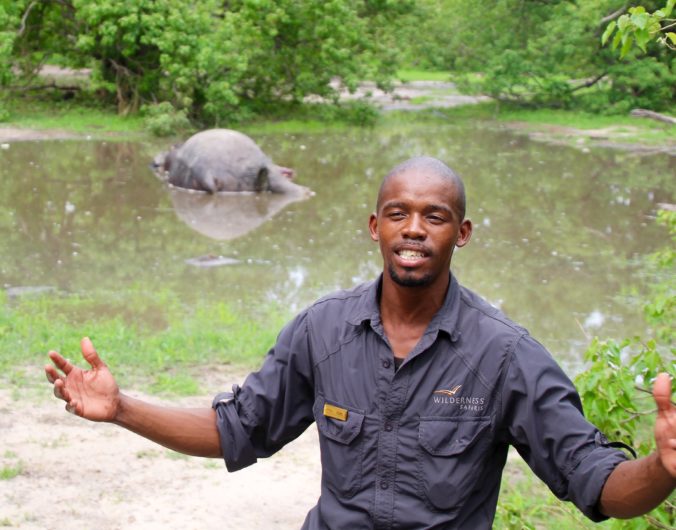

FjordPhyto connects Antarctic visitors with scientists in the Vernet Lab to help monitor changes in the microscopic life that thrive within coastal areas throughout November to March. Together they are learning how melting glaciers impact biodiversity and ecology at the base of the food web, while also increasing visitor engagement and understanding of science. Born and raised in Seattle, Washington Allison received her BS in Biology from the University of Washington in 2006, and her Masters in Marine Biodiversity & Conservation (at Scripps) in 2017. She spent the ten years in between working in various scientific fields before deciding to pursue a career as a polar oceanographer. Her first expedition to Antarctica was in 2013, where she boarded the US Nathaniel B Palmer as a research technician for 53-day expedition in the Ross Sea and that’s when the polar bug bit her. Her scientific expertise and love of travel have also allowed her to research exotic ecosystems in the Amazon jungle, the plains of Africa, and remote mountains in Mexico.

Feature image | Jack Pan; Other images | Allison Cusick

About IAATO

IAATO is a member organization founded in 1991 to advocate and promote the practice of safe and environmentally responsible private-sector travel to the Antarctic. IAATO Members work together to develop, adopt and implement operational standards that mitigate potential environmental impacts. These standards have proved to be successful including, but not limited to; Antarctic site-specific guidelines, site selection criteria, passenger to staff ratios, limiting numbers of passengers ashore, boot washing guidelines and the prevention of the transmission of alien organisms, wilderness etiquette, ship scheduling and vessel communication procedures, emergency medical evacuation procedures, emergency contingency plans, reporting procedures, marine wildlife watching guidelines, station visitation policies and much more. IAATO has a global network of over 100 members.

Share this:

Alone and unguarded, Brother lion ended up getting into some trouble. A band of three other brother lions roaming the area challenged him to a fight. Without the help of his brother, he was no match for the three males and unfortunately did not survive the attack.

Alone and unguarded, Brother lion ended up getting into some trouble. A band of three other brother lions roaming the area challenged him to a fight. Without the help of his brother, he was no match for the three males and unfortunately did not survive the attack. Each time we saw him, he barely moved. In the heat of the sun, you’d suspect he had died. Every now and then, though, he would stir, roll around, and clean himself off.

Each time we saw him, he barely moved. In the heat of the sun, you’d suspect he had died. Every now and then, though, he would stir, roll around, and clean himself off.

Then one evening, just before dusk, we saw Mr. Skinny in a rather peppy mood. We weren’t sure what was going on at first, but then we saw. Ms. Lion had returned. At first, she seemed rather annoyed he had started to follow her. She ran ahead, and he continued to slowly trot behind.

Then one evening, just before dusk, we saw Mr. Skinny in a rather peppy mood. We weren’t sure what was going on at first, but then we saw. Ms. Lion had returned. At first, she seemed rather annoyed he had started to follow her. She ran ahead, and he continued to slowly trot behind. It became clear he was too weak to catch up with her. Exhaustion took over, and he lay down to catch a break. Surely Ms. Lion would be on her way?

It became clear he was too weak to catch up with her. Exhaustion took over, and he lay down to catch a break. Surely Ms. Lion would be on her way?

The guides were optimistic that Mr. Skinny could recover. Although, with the band of three brothers still roaming around and a flirtatious female visiting them all, his chances would be slim unless he stayed well hidden from the other males.

The guides were optimistic that Mr. Skinny could recover. Although, with the band of three brothers still roaming around and a flirtatious female visiting them all, his chances would be slim unless he stayed well hidden from the other males.

Each day our schedule was full of adventure, food, and relaxation.

Each day our schedule was full of adventure, food, and relaxation.

Giraffes are probably one of my favorite animals. They’re so tall and slow. If you’ve ever seen a

Giraffes are probably one of my favorite animals. They’re so tall and slow. If you’ve ever seen a